by Lauren Mcmannus

Introduction

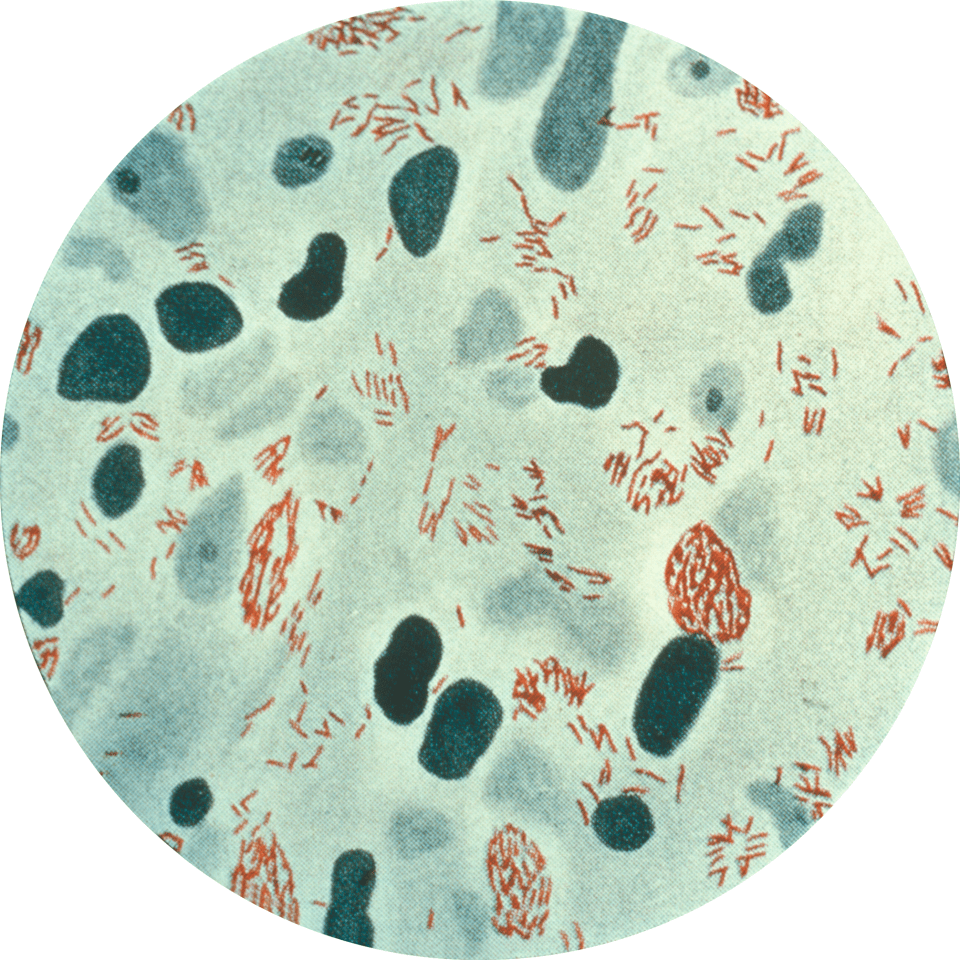

Bacillus anthracis is an endospore-forming bacteria that causes anthrax disease in animals and humans. The endospore (Figure 1) is the inactive, highly-resilient form of a B. anthracis bacterium that can withstand extreme conditions. Anthrax endospores enter its host most commonly through skin wounds, but also by inhalation or ingestion. Human contraction of B. anthracis occurs predominantly through contact with diseased animals or contaminated animal parts.

Figure 1: Image of Bacillus anthracis spores as seen under a microscope using phase contrast. Phase contrast shows endospores as bright white spots where the bacteria is dormant. Source: Public Health Image Library, Center for Disease Control, Larry Stauffer, Oregon State Public Health Laboratory (2002)

Disease

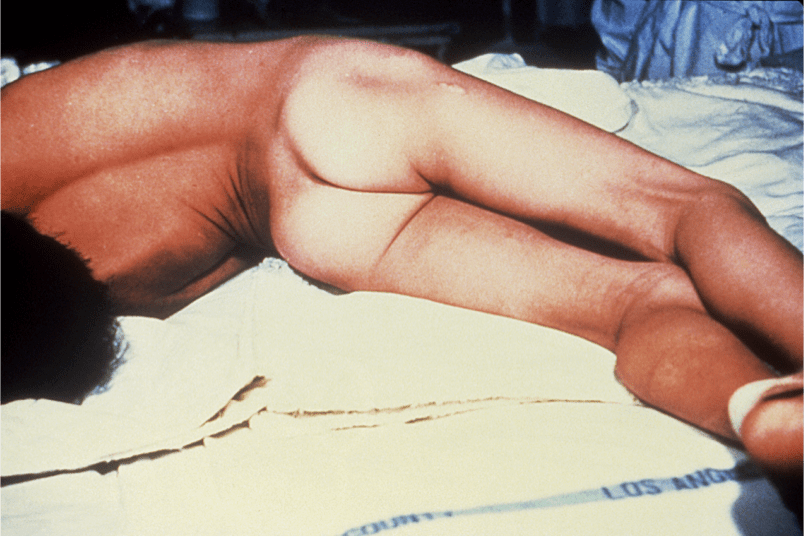

An infection develops in humans after exposure to B. anthracis in specific locations in the body depending on the route of exposure. Cutaneous anthrax occurs when bacteria enter skin through a wound or break in the skin, creating black lesions. Infection can also result from inhaling endospores released into the air from manufacturing wool or hides. Less commonly, anthrax infection can occur in the digestive system from eating contaminated food like undercooked and tainted meat, or through injection of heroin.

Once B. anthracis enters the human, the bacteria encounter macrophages, cells of the immune system that recognize bacterial pathogens and engulf them. Macrophages kill by trapping bacteria and exposing it to a highly acidic environment. These macrophages internalize the B. anthracis, but the endospores (Figure 1) are able to withstand these extreme conditions and survive. From there, B. anthracis can revert back to its non-spore state and replicate within the body, releasing toxins and causing damage.

Epidemiology

Rates of anthrax infection has significantly decreased in the past few decades, largely as a result of vaccine awareness and hygiene standards implemented around the world. Worldwide rates of infections are not well-recorded, but there are only 1 or 2 cases of cutaneous anthrax in the United States each year.

Humans have most commonly contracted anthrax after coming in contact with infected animals or animal products. Veterinarians, farmers, butchers, or industrial workers that handle animal hides or wool are at a higher risk of developing an infection, especially through a wound on the skin. More than 95% of all anthrax cases develop from cutaneous exposure, and this is also the least fatal as the infection is limited to one area.

Cutaneous exposure can have a mortality rate around 20%, while the mortality rates of inhalation and digestive system exposure are 80% and 25 to 75%, respectively. Internal anthrax infection is not as easily treated and is often not recognized until the disease is in its later stages, leading to high mortality rates.

Virulence Factors

When not in endospore form, B. anthracis is more susceptible to immune system defenses when travelling through the body. In order to disguise itself from the host’s immune system cells, like macrophages, B. anthracis surrounds itself in a capsule made up of poly-gamma-D-glutamic acid. When covered in this capsule, the bacteria are less likely to attract attention and can safely multiply and multiply.

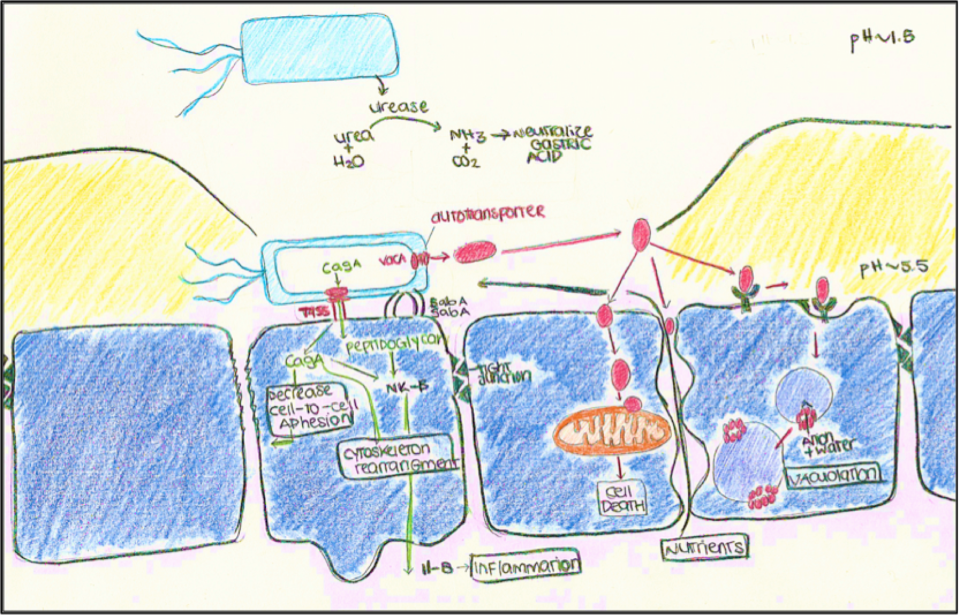

The damaging nature of B. anthracis is revealed when large numbers of these bacteria begin to release exotoxins. As seen in Figure 2, bacteria release protective antigen, edema factor, and lethal factor as three separate molecules that are not active by themselves. When the edema factor binds to the protective antigen, the edema factor becomes activated and causes fluid to rush out from cells and collect in the tissue. On the other hand, when the lethal factor binds to the protective antigen, a lethal toxin is created that helps kill macrophages and other cells of the immune system. It also changes the signals cells receive from each other, severely disrupting vital processes that allow for basic functions of cells and leading to cell death.

Figure 2: The secretion of inactive molecules by B. anthracis lead to the production of toxins. The binding of LF and EF alone do not create a toxin. The binding of LF and PA create an active lethal toxin, and the binding of PA and EF create an edema toxin. PA bound with both LF and EF have lethal and edema effects.

Prevention and Treatment

Though treatments are available, anthrax vaccines are available to humans and animals to offer the best protection against B. anthracis. Human vaccines are not available to the general population, but they are given to people working directly with animals or animal products that are at risk for infection.

Humans

Antibiotic treatments are available and useful when administered early, but they aren’t able to reverse the serious damage done by toxins. Infections can usually be treated with penicillin, an antibiotic that causes cell death by disrupting the links of peptidoglycan on a bacteria’s cell wall. Peptidoglycan is a molecule made up of proteins and sugars that form a protective layer around a bacterial cell.

However, other antibiotics like ciprofloxacin has been used in recent infections in the United States caused by the B. anthracis strain ‘Ames’, as these bacteria produce enzymes called beta-lactamases that can break down antibiotics like penicillin. Ciprofloxacin targets DNA gyrase and DNA topoisomerase IV, which are enzymes that regulate the coiling of bacteria DNA, and this targeting prevents proper DNA replication of B. anthracis.

Animals

Penicillin can also be used to treat animals, like cattle, that have contracted anthrax.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infections Diseases, Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases (2008, August 26 2009). Anthrax. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nczved/divisions/dfbmd/diseases/anthrax/technical.html#incidence

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015, September 1 2015). How People Are Infected. Anthrax. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/anthrax/basics/how-people-are-infected.html

Drlica, K., & Zhao, X. (1997). DNA gyrase, topoisomerase IV, and the 4-quinolones. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, 61(3), 377-392. Retrieved from http://mmbr.asm.org/content/61/3/377

FDA (Food and Drug Administration). (June 17 2015). Anthrax. Retrieved from http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ucm061751.htm

Jang, J., Cho, M., Chun, J.-H., Cho, M.-H., Park, J., Oh, H.-B., . . . Rhie, G.-e. (2011). The Poly-γ-d-Glutamic Acid Capsule of Bacillus anthracis Enhances Lethal Toxin Activity. Infection and Immunity, 79(9), 3846-3854. doi:10.1128/iai.01145-10

Organization, World Health. (2008). Anthraxin humans and animals (pp. 219). Retrieved from http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/anthrax_webs.pdf

Rogers Yocum, J. R. R., Jack L. Strominger. (1979). The Mechanism of Action of Penicillin. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, Vol. 255(No. 9), 3977-3986. Retrieved from http://www.jbc.org/content/255/9/3977.full.pdf

Schneemann A, Manchester M. Anti-toxin antibodies in prophylaxis and treatment of inhalation anthrax. Future microbiology. 2009;4:35-43. doi:10.2217/17460913.4.1.35.

Spencer, R. C. (2003). Bacillus anthracis. Journal of Clinical Pathology, 56(3), 182-187. doi:10.1136/jcp.56.3.182

Todar, K. (2012). Bacillus anthracis and Anthrax (page 3). Retrieved from http://textbookofbacteriology.net/Anthrax_3.html

Todar, K. (2012). Structure and Function of Bacterial Cells. Retrieved from http://www.textbookofbacteriology.net/structure_5.html