By Roxanne Losier and Giuliana Matta

Introduction

Taylorella equigenitalis is the pathogen known to cause contagious equine metritis (CEM), a sexually transmitted disease mostly targeting horses, but also seen in donkeys. This pathogen was first identified in 1977 in the United Kingdom, which then led to diagnosis in many other countries. T. equigenitalis is highly contagious and is considered a notifiable disease by the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE).

Disease

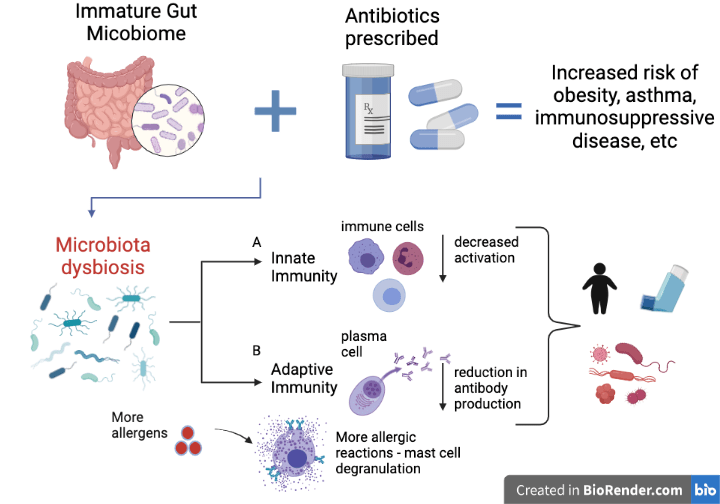

T. equigenitalis can be transmitted a number of ways such as during reproduction between an infected stallion and a mare, by contaminated equipment, or by infected semen used in artificial insemination. The primary site of infection of T. equigenitalis is the mare’s urogenital membranes, and it will not propagate through the mare’s body, since CEM is a nonsystematic infection. The infection can be characterized by mucopurulent vaginal discharge, a discharge containing mucus and pus, that can be observed as early as two days after contamination. Although one of the symptoms observed is an early return to estrus, the female’s menstrual cycle, an infection may result in a temporary loss of fertility for the mare. The symptoms typically disappear within days, however the mare may remain infected for several months. As for the stallion, the bacterium will shelter in the smegma of the prepuce and on the penis’ surface mostly in the urethral surface (Figure 1). Infected stallions will show no symptoms. While most infections will heal with no repercussions, the mare and the stallion can develop a chronic infection. In these cases, the pathogen will infect the clitoral fossa and sinuses of the mare and the stallion will simply remain a carrier (Figure 1). When the infection becomes chronic, both sexes will become asymptomatic, that is they will not show any symptoms of infections, making diagnosis much harder.

Figure 1: Site of infection of T. equigenitalis for the A. mare and B. stallion. Source: Roxanne Losier.

Epidemiology

Europe is the main continent affected by outbreaks of T. equigenitalis, and, in this area, it is characterized as an endemic disease. However, the presence of T. equigenitalis has never been detected in Canada, and the United States has successfully eradicated the bacterium. Therefore, they, and many other countries, are referred to as CEM-free countries. This status provides them a secure place within the trading market as well as an optimal reproductive efficiency.

In countries where outbreaks still occur, the main causative agent would be the reproduction of undiagnosed horses. Since T. equigenitalis is highly contagious, it is crucial to take the required prevention against this pathogen. For example, in 2000, an imported horse was an undiagnosed carrier for the disease. In a short period of 8 years, reported cases were found amongst 48 countries and a total of 1100 horses were reportedly exposed. Since the infection caused by T. equigenitalis does not lead to the death of the horse, the major impact of outbreaks would be economic. Indeed, the infected horses can no longer contribute to reproduction of the species for the period of the infection and must be properly treated for it not to become a chronic infection.

In order to be prepared in the case of an outbreak, Canada’s Government has prepared a protocol. This protocol was issued by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) and aims to eradicate the disease as soon as possible in order to re-establish Canada’s CEM-free country status. Some of the disease control methods include tracking of potentially infected horses, strict quarantine and treatment of infected horses and rigorous decontamination to redefine disease-free areas.

Virulence Factor

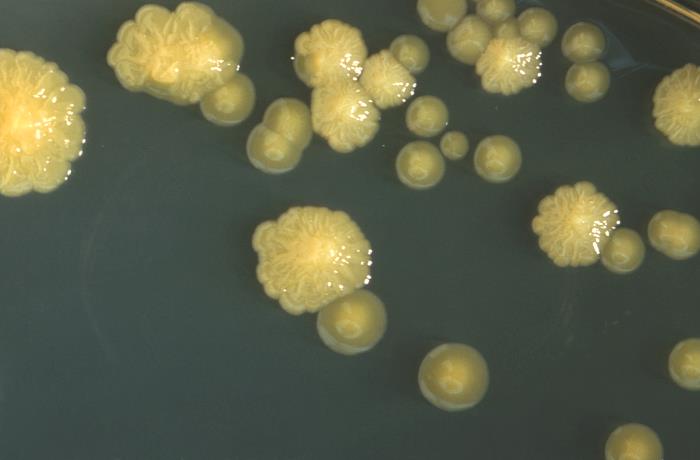

No virulence factors are known or confirmed since T. equigenitalis has fastidious growth requirements, meaning specific factors and conditions are needed for it to grow and survive in the laboratory. Additionally, the number of bacteria on the external genitalia of stallions is low, resulting in the disease to possibly be missed by culturing alone. Consequently, isolating and studying this disease is hard, thus discovering virulence factors becomes difficult, which can be one of the many reasons why no virulence factors have been documented. T. equigenitalis can also go unnoticed because the bacteria cause no harm to the host cells, essentially resulting in no damage to the external genitalia and the animals being asymptomatic. Given that the only animals concerned with this disease are mostly horses and occasionally donkeys, research is not rushed. Because the infection does not display direct harm to the tissues, the urgency to create a cure is low and therefore virulence factors are not identified.

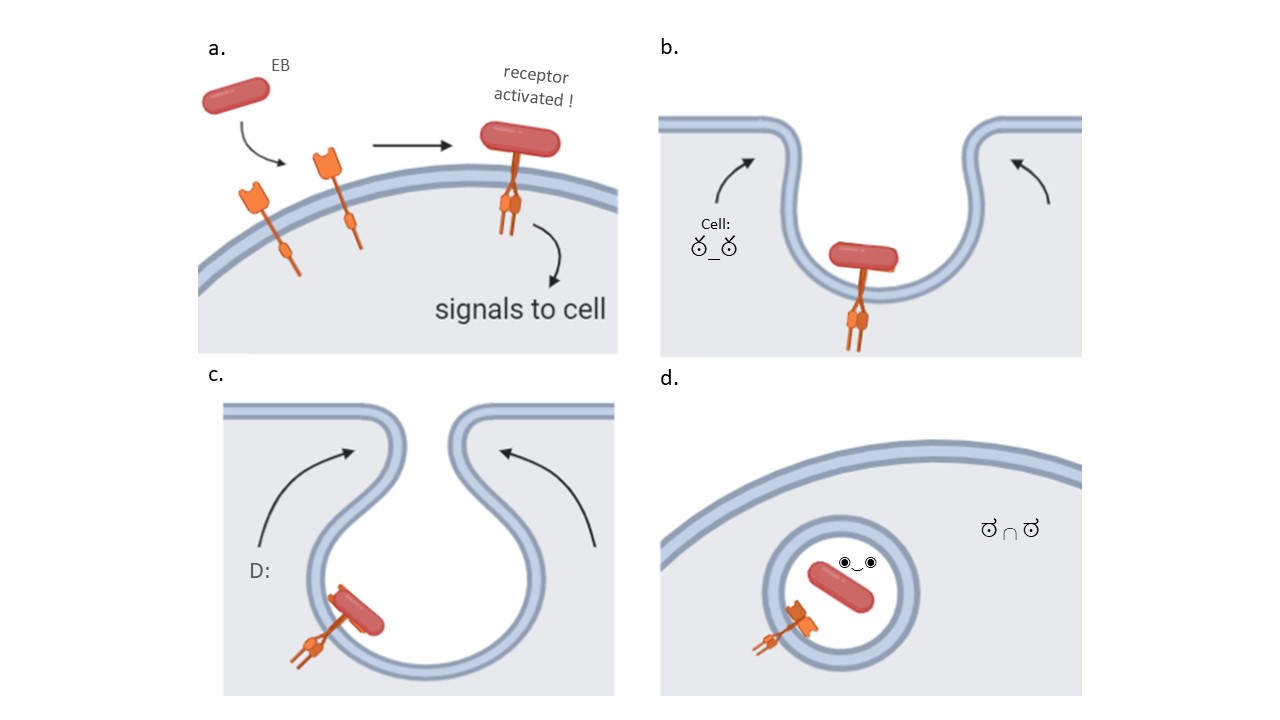

On the other hand, according to theory, we can hypothesize about a virulence factor that T. equigenitalis possesses. Adhesins are proteins located on the bacteria’ surface and aid in attachment to different places on the host cells’ surface by recognizing specific molecules (Figure 2). For T. equigenitalis to colonize the tissue, it must be able to recognize and bind to the cells of the external genitalia. With the adhesin proteins, the bacterium can bind and stay on the genitalia of horses and donkeys. Adhesins do not cause symptoms of the infection, but help the bacteria colonize in different niches, which is critical for the establishment of the infection. Therefore, it is very likely that T. equigenitalis contains adhesin proteins on its surface.

Figure 2: Adhesin proteins on T. equigenitalis. Source: Giuliana Matta

Treatment

As of today, no vaccine exists for T. equigenitalis, but treatments are available like disinfectants and antibiotics, which are provided topically. One antibiotic being ampicillin, which fights against certain Gram-negative organisms like T. equigenitalis. Even though this bacterium is sensitive to many antibiotics, no cure will completely eradicate and rapidly resolve the infection. In mares, the best treatment is performing daily washes for 5 days or more of the external genitalia. A 4% chlorhexidine solution, an antibacterial agent, is applied first, which clears the skin of infection and preps the area for the 0.2% nitrofurazone antibiotic ointment added afterwards, which fights Gram-negative bacteria. For stallions, the same procedures are implemented, but with 2% chlorhexidine solution instead of 4%. The application times for both mares and stallions varies depending on the severity of the disease. If the regimen does not work, they may have to remove the reproductive tract of the stallion or mare. In the end, the best way to prevent the transmission and the appearance of T. equigenitalis is to ensure the external genitalia of the animals are kept clean and to examine them for the disease because the horses or donkeys may be asymptomatic. Additionally, the animals should be assessed before entering any new stable or farm.

References

Castle, S.S. (2008). Ampicillin. xPharm: The Comprehensive Pharmacology Reference, (pp.1-6) Retrieved November 17, 2021, from https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-008055232-3.61227-9

Hébert, L., Moumen, B., Pons, N., Duquesne, F., Breuil, M. F., Goux, D., Batto, J. M., Laugier, C., Renault, P., & Petry, S. (2012). Genomic characterization of the Taylorella genus. PloS one, 7(1), e29953. Retrieved November 17, 2021 from, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0029953

Hitchcock, P. J., Brown, T. M., Corwin, D., Hayes, S. F., Olszewski, A., & Todd, W. J. (1985). Morphology of three strains of contagious equine metritis organism. Infection and immunity, 48(1), 94–108. Retrieved November 17, 2021 from, https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.48.1.94-108.1985

IBM Micromedex. (2021, October 1). Chlorhexidine (topical application route) precautions. Mayo Clinic. Retrieved November 17, 2021, from https://www.mayoclinic.org/drugs-supplements/chlorhexidine-topical-application-route/precautions/drg-20070874?p=1.

Luddy, S., & Kutzler, M. A. (2010). Contagious equine metritis within the United States: A review of the 2008 outbreak. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 30(8), 393–400. Retrieved November 17, 2021 from, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jevs.2010.07.006

OIE. (2018). Contagious Equine Metritis. Description and importance of disease – oie. Retrieved November 17, 2021, from https://www.oie.int/fileadmin/Home/eng/Health_standards/tahm/3.05.02_CEM.pdf.

Parlevliet, J. M., Bleumink-Pluym, N. M. C., Houwers, D. J., Remmen, J. L. A. M., Sluijter, F. J. H., & Colenbrander, B. (1997). Epidemiologic aspects of. Theriogenology, 47(6), 1169–1177. Retrieved November 17, 2021 from, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0093-691x(97)00097-6

Ricketts, S. W., Barrelet, A., Barrelet, F. E., & Stoneham, S. J. (2006). The stallion and mare reproductive system. The Equine Manual, 2(13), 713–763. Retrieved November 17, 2021 from, https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-7020-2769-7.50018-6

Rugbank. (n.d.). Nitrofural. Uses, Interactions, Mechanism of Action | DrugBank Online. Retrieved November 17, 2021, from https://go.drugbank.com/drugs/DB00336.

Timoney, P. J. (1996). Contagious equine metritis. Comparative Immunology, Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 19(3), 199–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-9571(96)00005-7.