by Rachel Vaughan and Cristina Mastromonaco

It begins…

Anthrax: it’s been plaguing humanity since… well, since the plagues. Bacillus anthracis has been

famously described by the Roman poet Virgil, and is suspected to have popped up as

the Plague of Athens and contributed to the fall of Rome. It brought medicine out of the dark ages: the study of anthrax gave definitive proof that contagious diseases can be attributed to a microorganism from a particular source, or reservoir, and was a pioneer in the field of vaccines [6].

Figure 1: Scientists are super creative! The word “anthrax” comes from the Greek word anthrakites, meaning “coal-like.” This is a tribute to the characteristic black scab that accompanies disease exposure, seen above. (Source 1: CDC 1962 ID#2033)

Look at me!

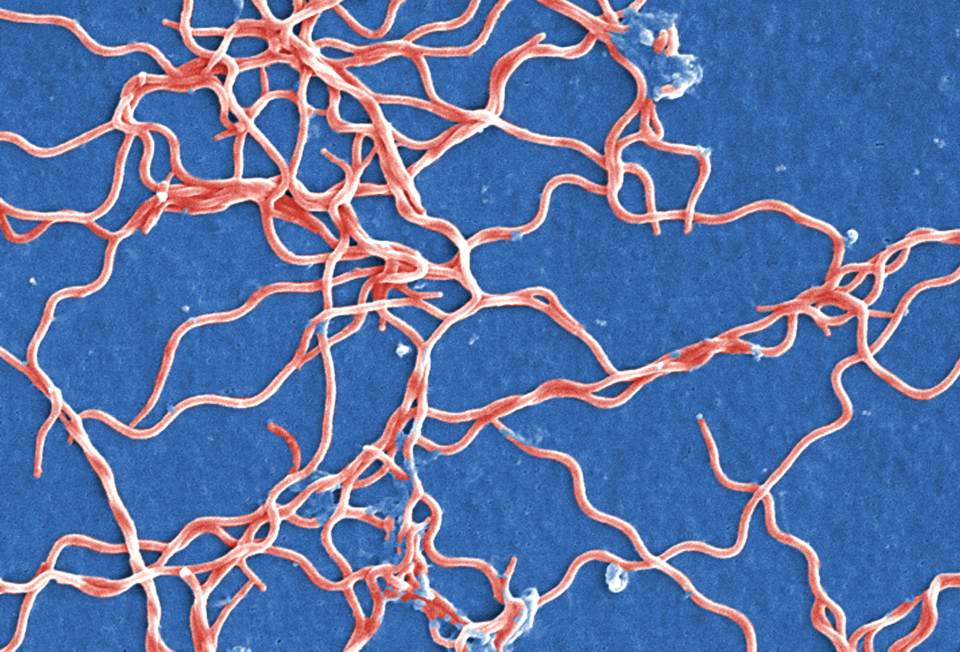

So just what is anthrax? To go textbook, it’s an aerobic, gram-positive (Fig 2), spore-forming bacteria that is naturally found worldwide in soil, with a preference for growing in warm, wet climates [1, 2]. That means that when conditions

So just what is anthrax? To go textbook, it’s an aerobic, gram-positive (Fig 2), spore-forming bacteria that is naturally found worldwide in soil, with a preference for growing in warm, wet climates [1, 2]. That means that when conditions  are suboptimal, anthrax can change from an actively replicating, rod shaped bacteria into a dormant endospore form, which can resist drying out, extreme heat, cold temperatures, ultraviolet light and disinfectants [1, 2]. Anthrax is a zoonotic bacteria that mainly affects the hoofed animal, but can be transmitted to humans through contaminated animal products [2].

are suboptimal, anthrax can change from an actively replicating, rod shaped bacteria into a dormant endospore form, which can resist drying out, extreme heat, cold temperatures, ultraviolet light and disinfectants [1, 2]. Anthrax is a zoonotic bacteria that mainly affects the hoofed animal, but can be transmitted to humans through contaminated animal products [2].

Figure 2: Gram-positive bacteria look purple under the microscope after they’ve been exposed to a series of dyes called a Gram Stain. A component in their cell wall binds to the violet dye, which in addition to making sure that they’re pretty for the Pathogen Ball, is the first step in helping you to identify these bacteria in a lab. (Source: CDC ID#2226)

Anthrax attacks

For someone to get infected with anthrax, the bacteria needs a way in. Cutaneous anthrax, ingestion anthrax and  inhalational anthrax are the three traditional modes of transmission. Your whole body is basically designed to try and fight this kind of thing, but anthrax is a really resourceful attacker. The body’s immune response does its best to protect you from these invaders, but it is no match for the anthrax spore [2].

inhalational anthrax are the three traditional modes of transmission. Your whole body is basically designed to try and fight this kind of thing, but anthrax is a really resourceful attacker. The body’s immune response does its best to protect you from these invaders, but it is no match for the anthrax spore [2].

Virulence factors allow a microorganism to cause disease, and anthrax has some good ones. It uses a combination of a capsule and potent exotoxins to evade and destroy. The capsule forms a protective shell around the growing bacteria, allowing it to get into host cells and use them like a taxi cab to travel to your lymph nodes, where it can spread through the blood [2].

Virulence factors allow a microorganism to cause disease, and anthrax has some good ones. It uses a combination of a capsule and potent exotoxins to evade and destroy. The capsule forms a protective shell around the growing bacteria, allowing it to get into host cells and use them like a taxi cab to travel to your lymph nodes, where it can spread through the blood [2].

![Figure 3: Anthrax releases its exotoxins (Fig 3.), the lethal factor and the edema factor, into the body. The protective antigen basically acts as a kind of Trojan horse, sitting on the surface of your body’s cells and smuggling them in to where they can do their damage. Edema factor makes the cell swell with water, while the lethal factor (again, scientists with their creative naming tactics) kills the cell by rupturing its membrane through a process called lysis. Similarly to how you don’t do too well when overfull or full of holes, neither do your cells, which is what makes anthrax such a dangerous player [2]. (Image by C. Mastromonaco).](https://mechpath.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/figure3.png?w=960)

Figure 3: Anthrax releases its exotoxins (Fig 3.), the lethal factor and the edema factor, into the body. The protective antigen basically acts as a kind of Trojan horse, sitting on the surface of your body’s cells and smuggling them in to where they can do their damage. Edema factor makes the cell swell with water, while the lethal factor (again, scientists with their creative naming tactics) kills the cell by rupturing its membrane through a process called lysis. Similarly to how you don’t do too well when overfull or full of holes, neither do your cells, which is what makes anthrax such a dangerous player [2]. (Image by C. Mastromonaco).

So, all of this seems like old news. Blah blah, thousands of years, blah blah different types, blah blah scary disease. But there’s something currently happening with anthrax spores, and it’s worth taking a look at even if the extent of your interaction with animals can be characterized by the words “they’re delicious.”

Just when we thought that anthrax was a thing of the past – the CDC estimates that only about two cases of naturally-occurring anthrax are documented each year [4] – we were given the gift of something new and wonderful to dread instead of sleeping. In their infinite wisdom, illicit drug users found a way to bring an already vicious bacteria to a whole new level: supplies of heroin contaminated with anthrax made their way into the general population, and subsequently into the arms, legs, butts and groins of some very unlucky addicts.

Bear with us here: we’re going to look at some numbers, compiled in a 2014 issue of Eurosurveillance. Injectional anthrax has exhibited what’s called a bimodal distribution: it first presented itself en masse in December 2009 (having only cropped up previously in a single case in the year 2000), and was followed by a second cluster of cases in June 2012. From 2009-2010, 126 cases of anthrax contracted by heroin users were reported, 95% of which were diagnosed in bonnie Scotland, which unfortunately doesn’t seem to be able to add “pure, unadulterated narcotics” to its list of tourist attractions. Between 2012 and 2013, 15 more cases have emerged in a half a dozen different European countries A 33% mortality rate was reported the first go-around, but the fatality in this more recent wave is much higher, with an estimated 47% of cases resulting in death (Fig. 4).

Bear with us here: we’re going to look at some numbers, compiled in a 2014 issue of Eurosurveillance. Injectional anthrax has exhibited what’s called a bimodal distribution: it first presented itself en masse in December 2009 (having only cropped up previously in a single case in the year 2000), and was followed by a second cluster of cases in June 2012. From 2009-2010, 126 cases of anthrax contracted by heroin users were reported, 95% of which were diagnosed in bonnie Scotland, which unfortunately doesn’t seem to be able to add “pure, unadulterated narcotics” to its list of tourist attractions. Between 2012 and 2013, 15 more cases have emerged in a half a dozen different European countries A 33% mortality rate was reported the first go-around, but the fatality in this more recent wave is much higher, with an estimated 47% of cases resulting in death (Fig. 4).

![Figure 4: This beautiful, color coded graph breaks down the timing and geography so that we don’t have to! You can see the two different clusters of disease presentation, and the different countries that were affected [6]. (Source: Eurosurveilance)](https://mechpath.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/figure4.jpg?w=960)

Figure 4: This beautiful, color coded graph breaks down the timing and geography so that we don’t have to! You can see the two different clusters of disease presentation, and the different countries that were affected [6]. (Source: Eurosurveilance)

uncommon, it doesn’t seem to elicit any of the standard markers for inflammation, like a higher number of white blood cells or elevated levels of C-reactive protein (CRP). It’s pretty weird – they suspect that it’s tied to the more immediate action of

uncommon, it doesn’t seem to elicit any of the standard markers for inflammation, like a higher number of white blood cells or elevated levels of C-reactive protein (CRP). It’s pretty weird – they suspect that it’s tied to the more immediate action of  the edema factor within the tissue, as it doesn’t have to cross the regular barriers [7]. So essentially, injectional anthrax presents most frequently as a kind of deep-tissue cutaneous anthrax with skin infection and blistering, but without any of the helpful markers for the disease that doctors look for. This, along with anthrax’s current state of “how on Earth would you get exposed to THAT?” led to some confusion and misdiagnosis, as the symptoms present similarly to a few other diseases.

the edema factor within the tissue, as it doesn’t have to cross the regular barriers [7]. So essentially, injectional anthrax presents most frequently as a kind of deep-tissue cutaneous anthrax with skin infection and blistering, but without any of the helpful markers for the disease that doctors look for. This, along with anthrax’s current state of “how on Earth would you get exposed to THAT?” led to some confusion and misdiagnosis, as the symptoms present similarly to a few other diseases.

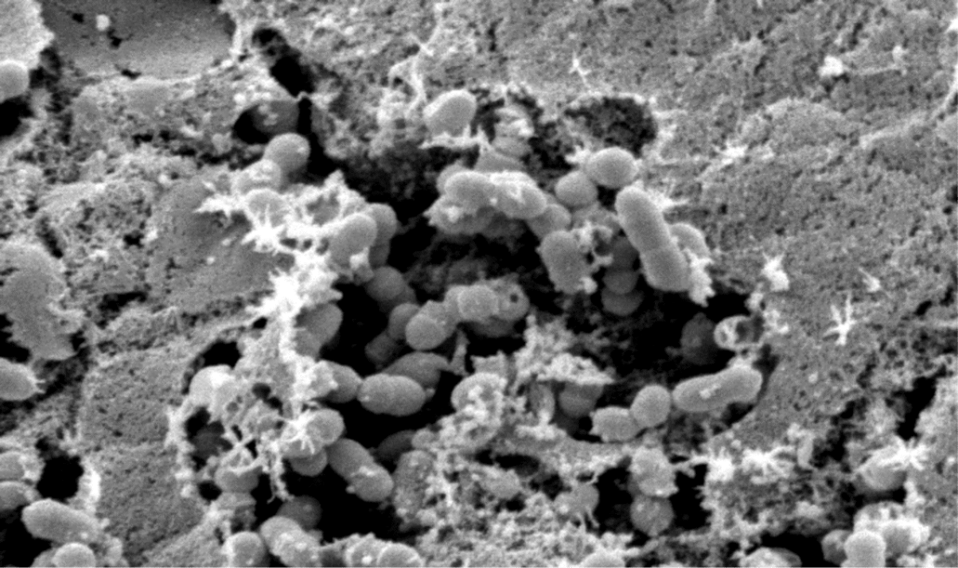

The most common cause of death was when the infection went systemic instead of being nicely localized in the injection site. Since the bacteria spread all throughout your body, systemic  anthrax often results in one of the most terrifying kinds of inflammation: meningitis (Fig. 5). There are three layers called the meninges wrapped around your brain and spinal cord. Large numbers of bacteria between the layers spells bad news for your brain, and in the case of anthrax, meningitis kills about 96% of the time [5]. Once the bacteria has gone systemic, it’s easy to see why it appeals to strongly to those in the heavy metal profession: the presence of large quantities of anthrax bacilli in your blood stream turns your blood so dark that it appears black.

anthrax often results in one of the most terrifying kinds of inflammation: meningitis (Fig. 5). There are three layers called the meninges wrapped around your brain and spinal cord. Large numbers of bacteria between the layers spells bad news for your brain, and in the case of anthrax, meningitis kills about 96% of the time [5]. Once the bacteria has gone systemic, it’s easy to see why it appeals to strongly to those in the heavy metal profession: the presence of large quantities of anthrax bacilli in your blood stream turns your blood so dark that it appears black.

Figure 5: This is your brain on anthrax: this poor soul suffered from hemorrhagic meningitis as a result of inhalation of the spores. Note the blackened outside of the brain, resulting from the anthrax-laden blood. (Source: CDC 1966 ID#1121)

The kicker is that despite the term “injectional anthrax,” at least two patients were likely infected by smoking the drug. That being said, those who smoked only had a much lower risk of developing the disease. That’s actually a pretty interesting development – despite having introduced the spores to their lungs, which would be ripe for colonization, respiratory symptoms were very rare.

Where did it come from, where will it go?

So, since anthrax is so uncommon in the modern world, just how did it worm its way into the European heroin supply? It was believed up until last month that all cases of injectional anthrax came from the same contamination in  Turkey, but this is unlikely to be the case. Genetically analyzing all available isolated strains (or isolates) of injectional anthrax suggests that there were at least two separate contamination events – one for each outbreak – as there are two different genetic clusters of anthrax bacilli. They’re not related closely enough on the anthrax family tree to have come from the same source, and according to their genetic makeup, they branched off at completely different times. The evidence does suggest that they come from the same country, but this is not necessarily true [9].

Turkey, but this is unlikely to be the case. Genetically analyzing all available isolated strains (or isolates) of injectional anthrax suggests that there were at least two separate contamination events – one for each outbreak – as there are two different genetic clusters of anthrax bacilli. They’re not related closely enough on the anthrax family tree to have come from the same source, and according to their genetic makeup, they branched off at completely different times. The evidence does suggest that they come from the same country, but this is not necessarily true [9].

Why do you care? Presumably the grand majority of you aren’t exactly the at-risk population. Sure, it’s scary for heroin users, who may be at risk for another spore contamination event, but what if your drug of choice is caffeine or ethanol? Since we don’t know exactly how the spores got into the heroin supply in the first place – via the smuggling route, from contaminated animal products used to bulk the heroin (like whatever it is they put into hotdogs) or from an intentional dose – there’s no way of predicting where contamination could go next. Anthrax may next find its way into any of the many imported products that you use in your daily life. Sugars, teas, oils or that gorgeous rug that you bought at the local market could easily be the next source of anthrax exposure to the general population.

References

[1] http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3523299/

[2] http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4073855/?report=classic

[3] http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19627991

[4] http://www.cdc.gov/nczved/divisions/dfbmd/diseases/anthrax/technical.html#trends

[5] http://www.thelancet.com/journals/laninf/article/PIIS1473-3099(05)70113-4/fulltext

[6] http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0736467903000799

[7] http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20877

[8] http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140673600031330

[9] http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352396415301705