by Jenna (Hyewon) Lee, Karen Wu

Introduction

On February 2002, a listeriosis outbreak was reported relating to Listeria monocytogenes contaminated soft-ripened cheeses in British Columbia, Canada. About 49 people reported symptoms of illness after consuming cheese products. The investigators figured out that the cheese products were all made from the same dairy plant which had a farm next to it. Collected cheese samples and stool samples were tested positive for L. monocytogenes strain. 43 people were admitted to hospital with infectious diarrhea; 3 people were diagnosed to have an inflammation of the membranes surrounding their brain. It was figured out that the onset of illness was on February 3rd. Immediately, all cheese products manufactured in this plant were recalled by Canadian Food Inspection Agency on February 13, 2002 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The timeline of the listeriosis outbreak. The x-axis is the date of the weekly illness onsets for confirmed and clinical listeriosis in this outbreak and the y-axis is the total number of cases. The onset of illness was on February 3rd and the recall date for all the cheese manufactured in this facility was on February 13th. 48 people were infected in this outbreak. Source: McIntyre L, Wilcott L, Naus M. 2015. Listeriosis outbreaks in british columbia, canada, caused by soft ripened cheese contaminated from environmental sources. BioMed Research International. 2015:12.

Description of listeriosis

Listeriosis is a bacterial infection caused by the genus Listeria. There are 6 species in the genus Listeria and the most common one is L. monocytogenes. This bacterium infects several organs in the body, including intestine, brain, and placenta. Once it gets into the body, it can cause multiple problems like inflammation of the brain tissues, presence of bacteria in the bloodstream, and even death. Listeriosis can also cause miscarriage in pregnant women. Newborn children, pregnant women, individuals who are over 65 years old, suffer from HIV, cancer, have transplanted organs, are generally more at risk of listeriosis.

Sources of outbreak

Most listeriosis cases are contracted through consumption of contaminated food. Several ready-to-eat foods have been the cause of listeriosis outbreaks including seafoods, deli meats, vegetables, fruits, unpasteurized and pasteurized dairy products. Control of L. monocytogenes is difficult because they can grow at environments that other bacteria cannot grow like low temperature (0°C), low pH (4.4), and high salt content (10%). Also, once L. monocytogenes is established in a food-processing plant, it can persist for years due to its ability to form biofilm which is highly resistant to sanitation. L. monocytogenes contamination in food-processing plants can happen during several different situations. It can happen during the transfer of raw milk into the processing facilities, by direct transfer from dairy animals to processing plants, or because of poor employee hygiene and sanitation (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Listeria can be found in various types of food including sprouts, meats, seafood, hot dogs, cheese, and milk (starting from the top left to the bottom right). They can also live in food processing plants for years by forming biofilm. Source: Jenna Lee (2017).

Cause of outbreak

The lack of proper management in the dairy plant caused the outbreak. The findings revealed that not only were the cheese aging rooms dirty, but untrained dairy plant workers incorrectly handled the culture spray bottles. The spray, which contained bacterial culture that gives flavor to the soft-ripened cheese and creates consistent rind on the outer surface of the cheese, had not been regularly washed and sanitized for months prior to the outbreak.

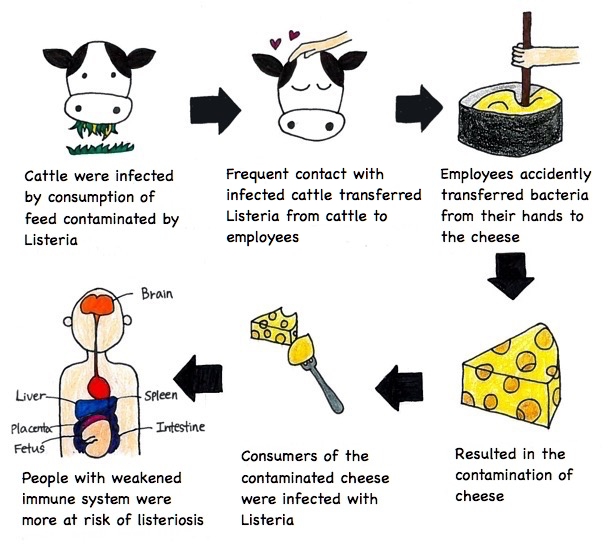

According to the investigations, another possible cause of this outbreak was the sharing of toilet facility between workers working on the farm and workers working in the dairy plant. Direct contact with farm animals or soils might have allowed the workers to carry L. monocytogenes on their clothes or shoes. The investigators hypothesized that some of the dairy workers might have transferred small clusters of Listeria into the culture spray bottles and as a result, L. monocytogenes grew in these spray bottles. Then the workers would have sprayed the culture onto the soft-ripened cheese, allowing the bacteria to grow in it (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Description of how the listeriosis outbreak happened. Source: Jenna Lee (2017).

Measures taken to end the outbreak

Two measures were proposed to minimize consumption of L. monocytogenes contaminated dairy foods and to lower the event of foodborne illnesses to the public. 1) Strict regulation and ongoing inspections should decrease the cross-contamination during the dairy processing procedures. Stringent monitoring and cleanliness would prevent the growth and dissemination of L. monocytogenes in the cheese products during post-pasteurization in soft-ripened cheeses. For example, dairy plants should limit the use of unpasteurized milk or raw milk to make soft ripened cheeses because pasteurization (high heat in short time) can kill L. monocytogenes. 2) Information about listeriosis was provided to advise the vulnerable populations such as the pregnant women, the elderly and the immunocompromised. L. monocytogenes is in many natural environments; it presents in the soil, water, vegetation, animal feedstuffs and food processing equipment. Hence, good practicing manners could easily eliminate the foodborne illnesses in human.

Aftermath

After the outbreak, British Columbia provincial authorities recommended the dairy processing factory involved in the outbreak to test for L. monocytogenes before selling their products. Also, they made a new requirement for periodic testing of soft ripened cheese products made outside BC for L. monocytogenes. All dairy processing factories were required to submit food safety plans, product lists for their operations, and how the environment of their factory looked like. BC further enhanced inspection, recommending diary and public health inspectors to regularly test for the presence of L. monocytogenes in the facilities, report the source of water the facilities were using, and check whether the ripening solutions were controlled under the food safety plans.

References

Galanis E, Shyng S. 2009. Listeriosis outbreaks in Canada in 2008 [Internet]. Delta (BC): BC Food Protection Association; [cited 2017 Nov 15]. Available from: http://bcfpa.net/Attachments/Presentations/Listeriosis%20outbreaks%20in%20Canada%20in%202008%20(E%20Galanis%20&%20S%20Shyng)%2019%20Jan%202009.pdf.

Kovacevic J, McIntyre LF, Henderson SB, Kosatsky T. 2012. Occurrence and distribution of listeria species in facilities producing ready-to-eat foods under provincial inspection authority in British Columbia, Canada. Journal of food protection. 75(2): 216-224.

McIntyre L, Wilcott L, Naus M. 2015. Listeriosis outbreaks in British Columbia, Canada, caused by soft ripened cheese contaminated from environmental sources. BioMed Research International. 2015:12.

Rodrigues CS, Cordeiro de Sá CGV, Barros de Melo C. 2017. An overview of listeria monocytogenes contamination in ready to eat meat, dairy and fishery foods. Ciência Rural, 47(2).

Sauders BD, D’Amico DJ. 2016. Listeria monocytogenes cross-contamination of cheese: risk throughout the food supply chain. Epidemiology and Infection. 144(13):2693-2697.

Taylor M, Bitzikos O, Galanis E. 2008. Listeriosis awareness among pregnant women and their health care providers in British Columbia. BCMJ. 50(7): 398-399.

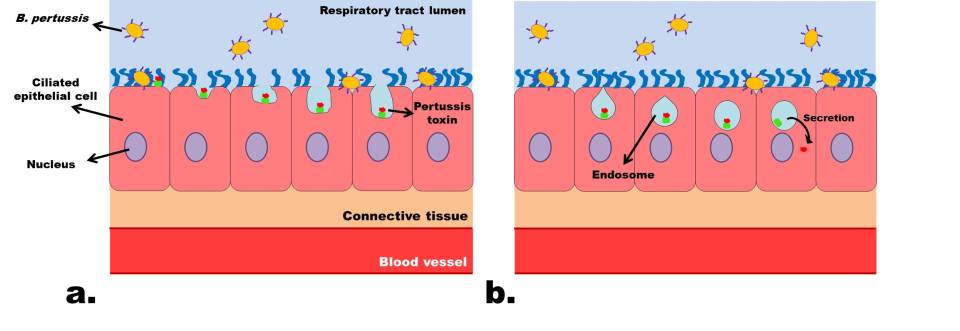

Figure 1: Drawing showing the effect of Bordetella pertussis on the ciliated epithelial cells in the respiratory tract. A, normal state of epithelium with regular ciliary function; B, degradation of cilia and breakdown of cells following toxin secretions by B. pertussis. (Source: Wing Chi Cheng)

Figure 1: Drawing showing the effect of Bordetella pertussis on the ciliated epithelial cells in the respiratory tract. A, normal state of epithelium with regular ciliary function; B, degradation of cilia and breakdown of cells following toxin secretions by B. pertussis. (Source: Wing Chi Cheng)

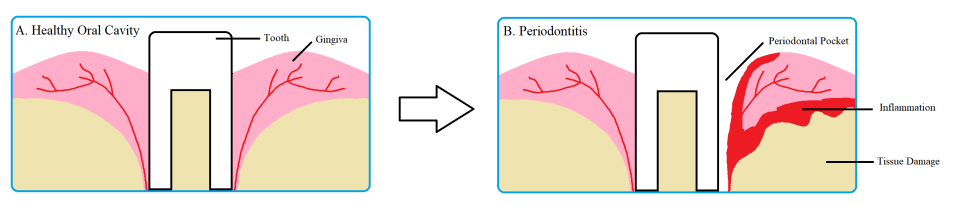

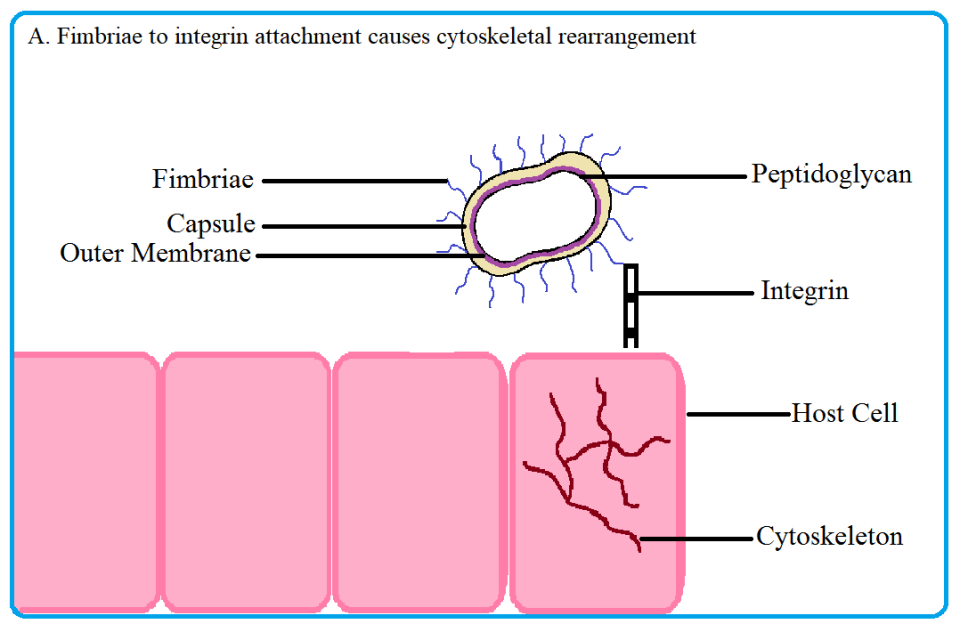

Fig 2. Porphyromonas gingivalis uses its fimbriae to attach to integrin molecules on the host surface and enter the cell. Upon fimbriae and integrin binding, the cytoskeleton of the host cell rearranges, allowing the pathogen to enter. Once inside, the bacterium induces autophagy in the host to create a nutrient rich niche to replicate in. Source: Thomas Donoso and Dennis Park.

Fig 2. Porphyromonas gingivalis uses its fimbriae to attach to integrin molecules on the host surface and enter the cell. Upon fimbriae and integrin binding, the cytoskeleton of the host cell rearranges, allowing the pathogen to enter. Once inside, the bacterium induces autophagy in the host to create a nutrient rich niche to replicate in. Source: Thomas Donoso and Dennis Park.

Figure 2: Transfer of effector proteins from bacterium to inside of host cells by type-3 secretion system. VopQ is red, VPA0450 is pink, and VopS is yellow. Adapted from “Vibrio parahaemolyticus cell biology and pathogenicity determinants” by Boberg et al,2011 .

Figure 2: Transfer of effector proteins from bacterium to inside of host cells by type-3 secretion system. VopQ is red, VPA0450 is pink, and VopS is yellow. Adapted from “Vibrio parahaemolyticus cell biology and pathogenicity determinants” by Boberg et al,2011 .