by Ruolin Yan

Introduction

Yersinia enterocolitica is a food-borne pathogen which causes a disease called yersiniosis in animals and humans, infants and young children are particularly affected. To be more specific, the most frequent form of yersiniosis is gastroenteritis or inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract. It is widespread in nature, and is present in aquatic systems, soil and gastrointestinal tracts of a variety of higher vertebrates, particularly pigs.

Disease

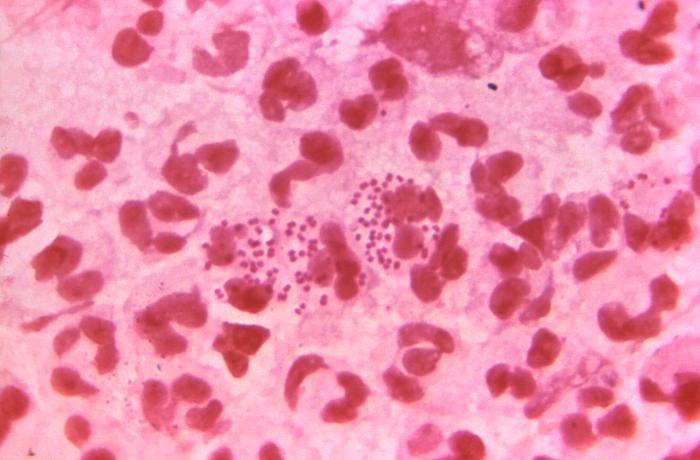

After ingestion of contaminated food, most often pork, Y. enterocolitica first travels to the small intestine using a structure called flagella (Figure 1) and invades the intestinal epithelial cells using M cells as an entry point. M cells are special epithelial cells located in a region called Peyer’s patches that sample the gastrointestinal tract for potential disease-causing bacteria or pathogens. After invasion, the bacterium replicates and reproduces inside Peyer’s patches, which are lymphatic tissue found in the small intestine. The bacteria can also spread from there to mesenteric lymph nodes, which is also part of the lymphatic system. This causes mesenteric lymphadenitis, which is characterized by inflammation of the lymph nodes. Overall, Y. enterocolitica causes a range of disorders ranging from mild gastroenteritis to more severe lymph node inflammation. Symptoms include fever, diarrhea, vomiting and abdominal pain.

Figure 1: Y. enterocolitica travelling to the small intestine using flagella (a structure that allows the bacteria to move). Source: Ruolin Yan.

Epidemiology

Yersiniosis can be transmitted from animals to humans, this is called zoonosis, which is animal infectious disease that can be transmitted to humans. Pork and pork products are an important reservoir for transmission. However, dog, cat, sheep and wild rodent are also possible reservoirs of pathogenic Y. enterocolitica. The most common transmission route is speculated to be pork products contaminated with pig feces.

Most cases of yersiniosis are sporadic, that is, they do not share a common source. Y. enterocolitica is a major cause of gastrointestinal disease in many developed countries. In United States, incidence of Yersiniosis appears to be lower compared with many European countries. However, in many developing countries such as Bangladesh, Iraq, Iran and Nigeria, gastrointestinal disease including Yersiniosis is also observed to be highly prevalent, which is related to food safety problem.

Virulence factors

After ingestion of contaminated food, Y. enterocolitica is challenged by high acidity of the stomach, this problem is resolved by an enzyme produced by the bacteria which raises the pH. Then, the bacterium travels to the small intestine, attaches to the epithelial layer, and invades the intestinal barrier via M cells. Adherence and invasion is mediated by two genes, inv (invasion) and ail (attachment).

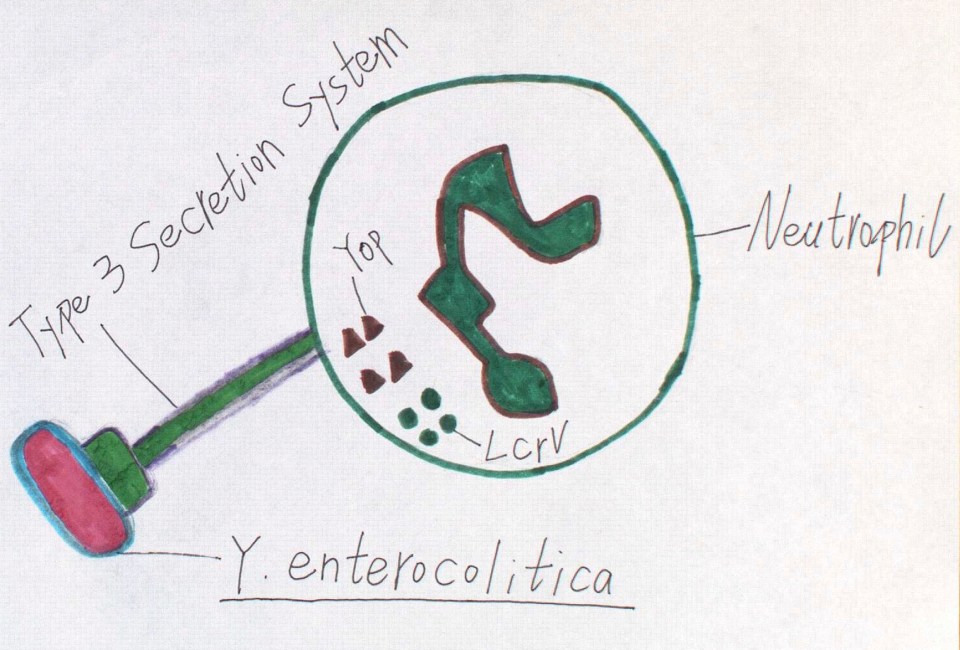

Once established inside Peyer’s patches, bacteria are normally killed by neutrophils there, which are cells that are specialized in digesting and clearing bacteria. This is accomplished by a process called phagocytosis. During phagocytosis, neutrophils engulf bacteria. At this point, bacteria are inside a membrane compartment called phagosome. Subsequently, they will be killed and digested by enzymes, etc. However, in the case of Y. enterocolitica, they resist phagocytosis. This is due to several proteins that are exported by them and injected directly into neutrophil, such as Yops and LcrV proteins. This is achieved by type 3 secretion system, which is a secretion system that forms a channel spanning from the interior of the bacteria to interior of the neutrophil (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Y. enterocolitica resisting phagocytosis by neutrophil through injection of Yop and LcrV proteins via a type 3 secretion system. Source: Ruolin Yan

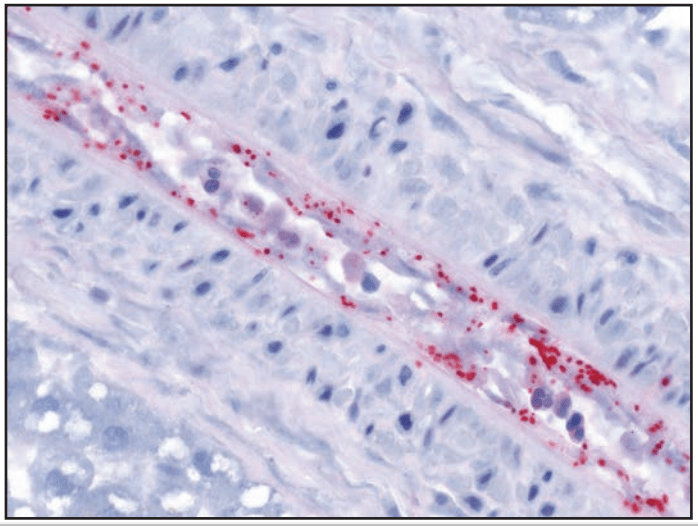

Even though Y. enterocolitica multiplication usually happens outside the cell, evidence suggests that it can survive and multiply in macrophages (another type of cell capable of performing phagocytosis) found in Peyer’s patches, which is likely to be the most important at early stage of infection. Normally, once inside the phagosome through phagocytosis, pumping of toxic compounds and release of free radicals kills the bacteria. This requires decrease in pH inside the phagosome in order to activate the proteins. Nevertheless, in the case of Y. enterocolitica, decrease in pH is inhibited, probably through lowering the activity of V-ATPase, an enzyme involved in pumping protons in and decreasing the pH.

Treatment

Yersiniosis is usually diagnosed by detecting bacteria in stools. Generally, most intestinal illnesses do not require treatment, because patients generally recover without treatment. However, in cases of severe or complicated infections, use of antibiotics should be considered. There is a range of antibiotics to which Y. enterocolitica is sensitive to, one of them is tetracycline. Tetracycline is bacterial protein synthesis inhibitor, which acts by binding to bacterial ribosome, which is a structure necessary for protein synthesis. As a result, Y. enterocolitica are not able to synthesize proteins, including those that are necessary to fight phagocytosis. To protect yourself from Yersiniosis, it is very important not to eat uncooked or undercooked pork. It is also important to avoid consuming unpasteurized milk and milk products.

References

Białas, N., Kasperkiewicz, K., Radziejewska-Lebrecht, J., & Skurnik, M. (2012). Bacterial cell surface structures in Yersinia enterocolitica. Archivum Immunologiae et Therapiae Experimentalis, 60(3), 199-209.

Chopra, I., & Roberts, M. (2001). Tetracycline antibiotics: mode of action, applications, molecular biology, and epidemiology of bacterial resistance. Microbiology and molecular biology reviews, 65(2), 232-260. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.65.2.232-260.2001

Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2016). Yersinia enterocolitica (Yersiniosis). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/yersinia/faq.html

Dhar, M. S., & Virdi, J. S. (2014). Strategies used by Yersinia enterocolitica to evade killing by the host: thinking beyond Yops. Microbes and infection, 16(2), 87-95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micinf.2013.11.002

Falcao, J. P., Brocchi, M., Proença‐Módena, J. L., Acrani, G. O., Correa, E. F., & Falcao, D. P. (2004). Virulence characteristics and epidemiology of Yersinia enterocolitica and Yersiniae other than Y. pseudotuberculosis and Y. pestis isolated from water and sewage. Journal of applied microbiology, 96(6), 1230-1236. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02268.x

Fredriksson-Ahomaa, M., Stolle, A., & Korkeala, H. (2006). Molecular epidemiology of Yersinia enterocolitica infections. FEMS Immunology & Medical Microbiology, 47(3), 315-329. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-695X.2006.00095.x

Rahman, A., Bonny, T. S., Stonsaovapak, S., & Ananchaipattana, C. (2011). Yersinia enterocolitica: Epidemiological studies and outbreaks. Journal of pathogens, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.4061/2011/239391

Watanabe, K., Watanabe, N., Jin, M., Matsuhashi, T., Koizumi, S., Onochi, K., … Mashima, H. (2014). Mesenteric lymph node abscess due to Yersinia enterocolitica: case report and review of the literature. Clinical journal of gastroenterology, 7(1), 41-47.

Pujol, C., & Bliska, J. B. (2005). Turning Yersinia pathogenesis outside in: subversion of macrophage function by intracellular yersiniae. Clinical Immunology, 114(3), 216-226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2004.07.013

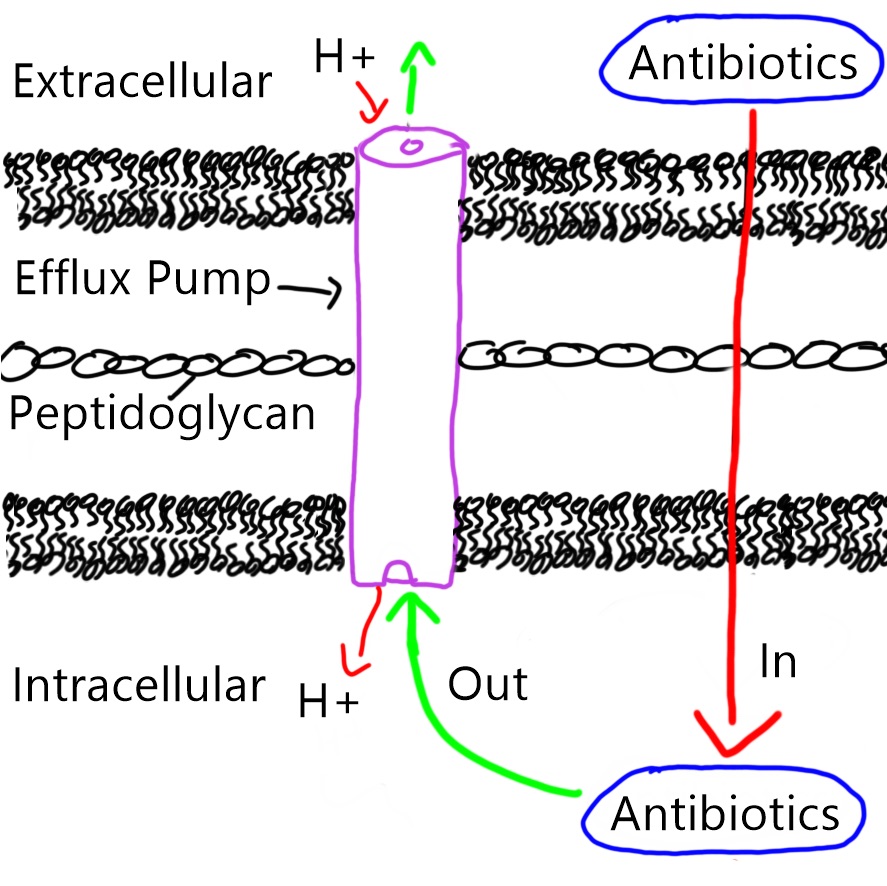

Figure 2. Efflux pump in the bacterial membrane pumps antibiotics out of the bacteria, passing through the inner, peptidoglycan and outer membranes in an anti-port manner (protons goes in, antibiotics goes out).

Figure 2. Efflux pump in the bacterial membrane pumps antibiotics out of the bacteria, passing through the inner, peptidoglycan and outer membranes in an anti-port manner (protons goes in, antibiotics goes out). Figure 1: Botulism cases (n = 31) in a federal correctional facility in Mississippi by reported date of hooch exposure and symptom onset between June 1–19, 2016. Source: McCrickard, L. et al. (2017).

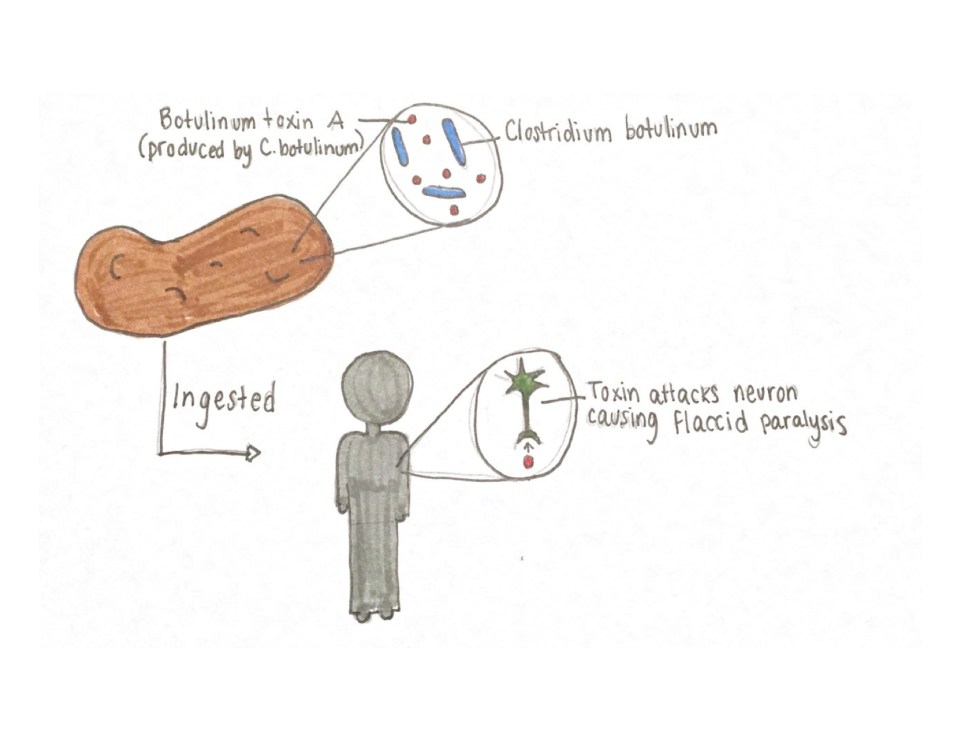

Figure 1: Botulism cases (n = 31) in a federal correctional facility in Mississippi by reported date of hooch exposure and symptom onset between June 1–19, 2016. Source: McCrickard, L. et al. (2017). Figure 2: Illustration of the foodborne botulism pathway showing that BoNT must be produced in food by C. botulinum and, subsequently, ingested by way of the food for symptoms to occur in an individual. Source: Hailey Pelland (2017).

Figure 2: Illustration of the foodborne botulism pathway showing that BoNT must be produced in food by C. botulinum and, subsequently, ingested by way of the food for symptoms to occur in an individual. Source: Hailey Pelland (2017).