By Laetitia Gaurier and Danaelle Page

Introduction

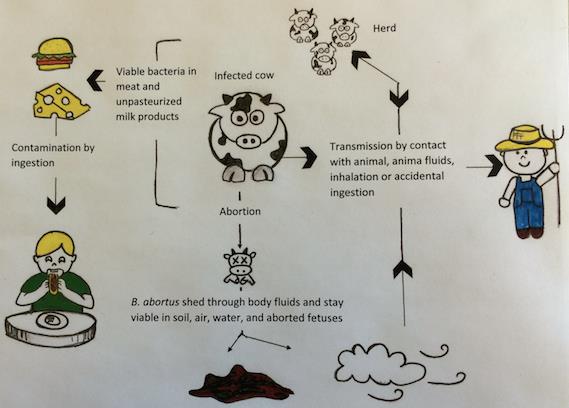

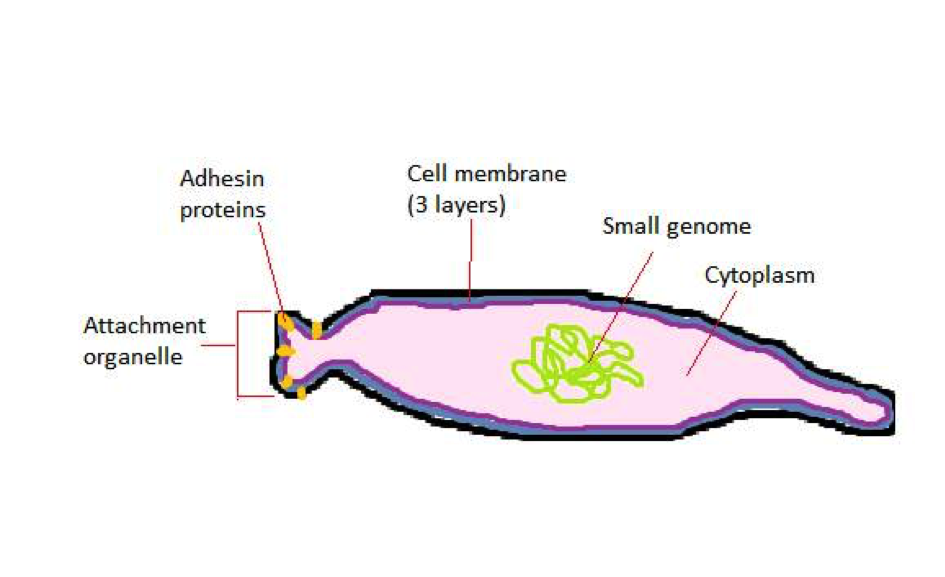

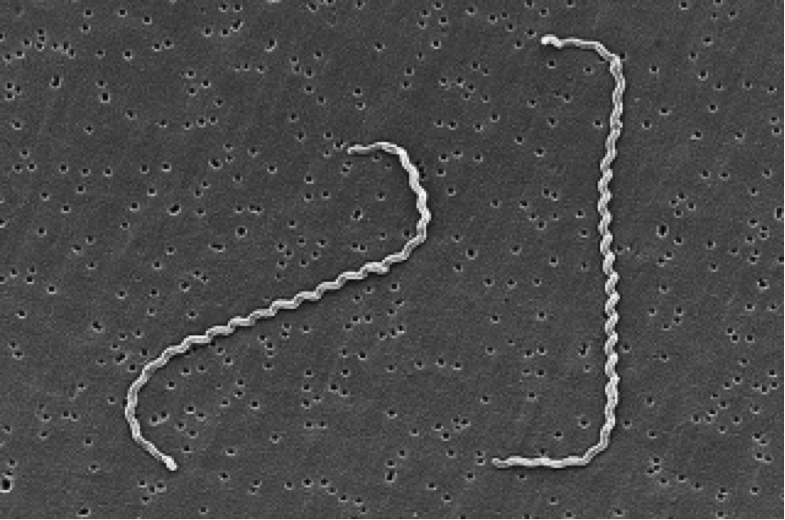

Leptospira interrogans causes leptospirosis. This disease is a zoonosis affecting many animal species and it can be transmitted to humans. These agents of disease, called leptospires, are a type of spirochetes, highly motile cylindrical cell bodies that grow in presence of oxygen and use axial filament rotation for motility (see Figure 1). L. interrogans is found worldwide, but mostly in hot and humid regions (e.g Asia, Latin America and Africa). This species encompasses many serovars, i.e a distinguishable variant of L. interrogans that can be pathogenic (cause disease) or not.

Figure 1. Scanning Electron Micrograph of Leptospira interrogans. Two spirochetes are bound to a 0.2-μm filter. Notice the coiling of the cell. Source: CDC/NCID/HIP/Janice Carr,

doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030302.g001.

Disease

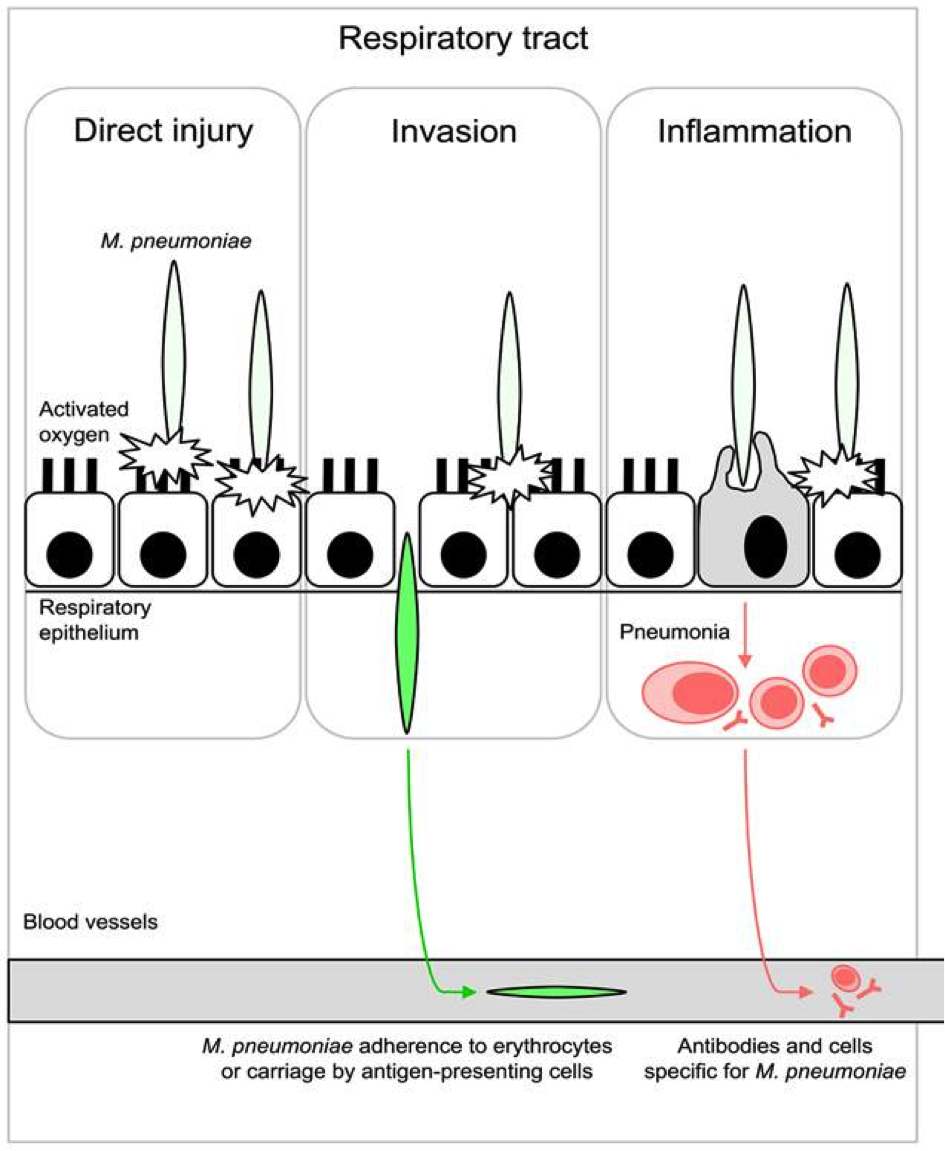

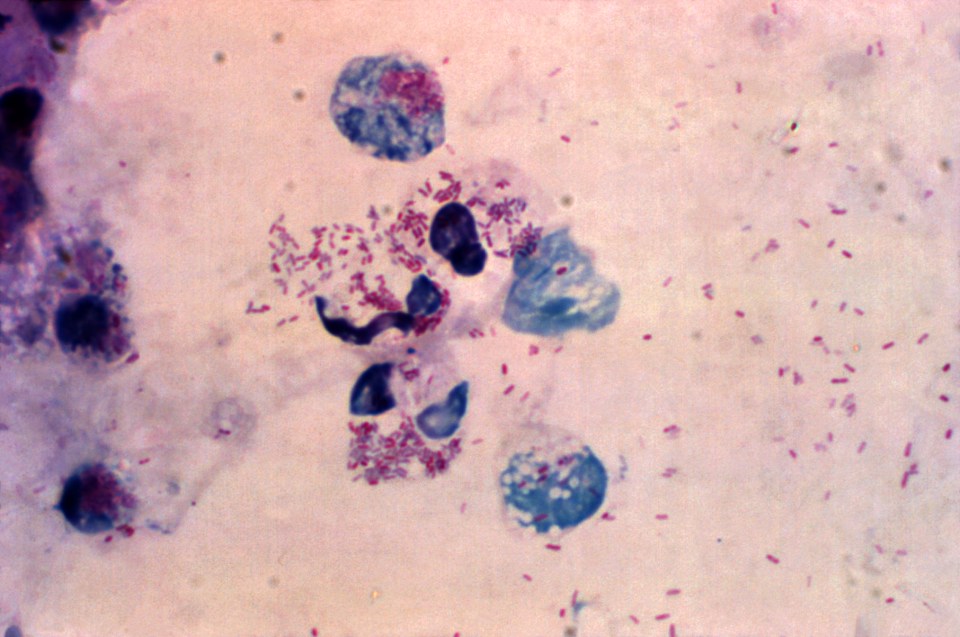

L. interrogans can be transmitted to humans by skin or mucosal contact with urine-contaminated soil or fluids from contaminated animals (see Figure 2). Leptospires migrate through the host tissues, invade cells and reach important organs of mammals. They activate macrophages, immune cells that protect the host by eating and digesting anything foreign encountered. Activation happens through binding of bacterial surface receptors that elicit the host immune response. Antibodies specific for lipids exposed on the bacterial membrane (lipopolysaccharides) are secreted against the leptospires and provide protection against reinfection.

Figure 2: Leptospirosis transmission route. Reservoir for L. interrogans transmission include rodents species, wild and domestic animals, as well as contaminated environment. Humans are accidental hosts and do not spread the microorganism in the environment ; they are not reservoirs for transmission. Pathogenic leptospires penetrate wounded skin or mucous membranes, enter the bloodstream and disseminate throughout the body tissue.

Adapted from: Ko, A.I., Goarant, C. and Picardeau, M. 2009. Leptospira: the dawn of the molecular genetics era for an emerging zoonotic pathogen. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 7: 736-747. Available from: DOI: 10.1038/nrmicro2208

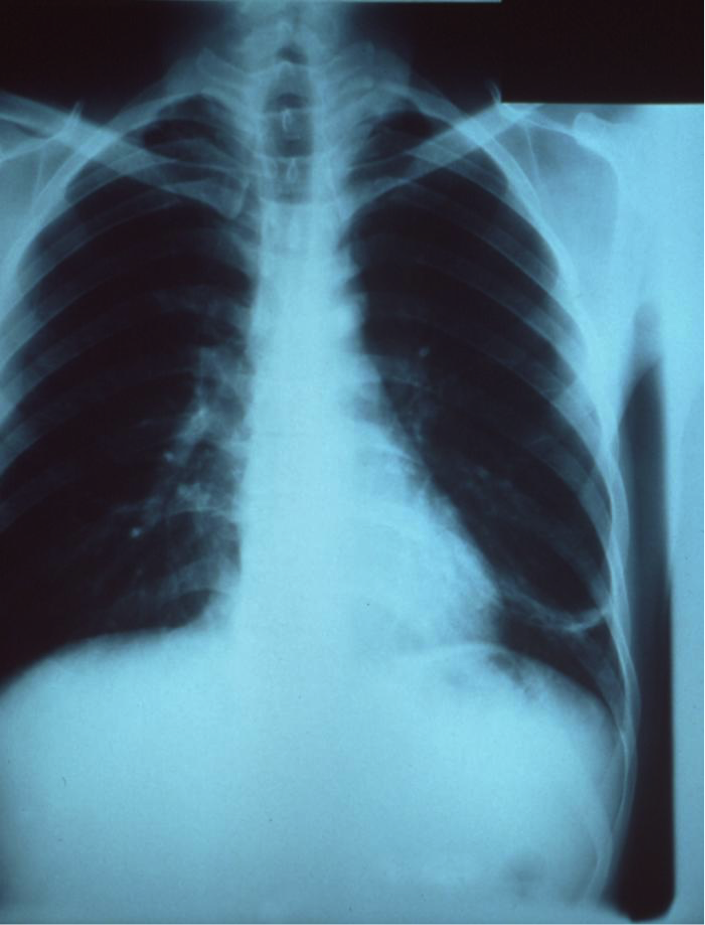

Symptoms of leptospirosis vary greatly: asymptomatic, fever, affected liver, lungs or kidneys. In extreme cases, it can result in multiple organ failure. This disease presents itself either as Weil’s disease (jaundice form), or as icteric plurivisceral form (jaundice and many organs affected). The latter progresses through three phases:

1) The asymptomatic incubation phase; leptospires gain the bloodstream.

2) The pre-icteric phase or the invasion of the host tissues.

3) The icteric phase where non-specific antibodies appear and symptoms increase and decrease.

Leptospirosis is usually poorly diagnosed due to the large variety and non-specificity of symptoms. Many methods of diagnosis exist, but the three most common are: polymerase chain reaction (PCR), microscopic agglutination test (MAT) and rapid genus-specific tests. The PCR method detects leptospires’ DNA in the analyzed patient sample. The MAT technique is the reference test; it detects antibodies against leptospires present in the sample. Rapid genus-specific tests are faster than MAT method at detecting unspecific antibodies, but complete diagnosis requires confirmation with the MAT technique.

Epidemiology

Leptospirosis represents a public health threat as a potential epidemic and newly emerging infectious disease. Reservoirs of this zoonosis include rodents, livestock and dogs (see Figure 2). Its incidence is normally higher in tropical and subtropical areas like South America due to climatic conditions; outbreaks from various serovars have been linked to floods, hurricanes or heavy rainfall. The number of cases worldwide is not known precisely, partly due to difficulties in establishing clear diagnosis, but recent estimates indicate more than 500,000 cases annually reaching 10% mortality. Leptospirosis may be an occupational hazard through direct or indirect urine contact. This transmission mode threatens pit workers, outdoors workers like farmers and animal contact workers like veterinarians. This disease also represents a recreational hazard for swimmers. For example, several leptospirosis outbreaks occurred following triathlons.

Virulence factors

L . interrogans different serovars have their own virulence factors suspected to play a role in leptospirosis causation. Among these virulence factors, we find toxin production. A toxin is a poisonous substance secreted by a pathogenic bacterium to harm host cells. Haemolysins, a toxin category, lyse or burst host red blood cells and are produced by L. interrogans. Bacterium attachment to host epithelial cells (i.e cells covering body surfaces such as skin, mucosa, etc.) also represents a virulence factor. L. interrogans especially attaches to renal epithelial cells, but host immune cells such as macrophages can fight this by engulfing invading bacteria. Surface proteins (lipopolysaccharides) allow L. interrogans to be recognized as pathogenic by macrophage and elicit an immune response. This response consists of antibodies production; those target and attack specifically the infecting leptospires. However, our bacterium defends itself by killing macrophages through elevation of their intracellular calcium levels. Last but not least, host antibodies may harm the host itself since L. interrogans can disappear from bloodstream. Antibodies could start attacking host red blood cells or platelets; this last virulence factor is immune-mediated and aggravates disease symptoms.

Treatment

Various antibiotics usually clear L. interrogans depending on the gravity of the infection (e.g penicillin (or penicillin G), doxycycline, ampicillin and amoxicillin). A few new antibiotics are being tested (e.g cefepime, ertapenem, norfloxacin). All antibiotics used and tested so far seem to control the disease. Also, vaccines made from killed bacteria are used in humans and animals to promote temporary immunity against leptospirosis.

References

Assez, N., Mauriaucourt, P., Cuny, J., Goldstein, P. and Wiel, E. 2013. Ictère fébrile… et si c’était une leptospirose. À propos d’un cas de L. interrogans Icterohaemorrhagia dans le Nord de la France. Annales Françaises d’anesthésie et de Réanimation. 32: 439-443.

Bharti, A.R., Nally, J.E., Ricaldi, J.N., Matthias, M.A. et al. 2003. Leptospirosis : a zoonotic disease of global importance. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 3: 757-771.

Haake, D.A. and Levett, P.N. 2015. Leptospirosis in Humans. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. 387: 65-97. Available from: DOI: 10.1007/978-3-662-45059-8_5

Lee, S.H., Kim, K.A., Park, Y.G., Seong, I.W., Kim, M.J and Lee, Y.J. 2000. Identification and partial characterization of a novel hemolysin from Leptospira interrogans serovar lai. Gene. 254(1-2): 19-28. Available from: DOI: 10.1016/S0378-1119(00)00293-6

Levett, P.N. 2001. Leptospirosis. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 14(2): 296-326. Available from: DOI: 10.1128/CMR.14.2.296-326.2001

World Health Organization. 2003. Human Leptospirosis: Guidance For Diagnosis, Surveillance And Control. Malta. Retrieved from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42667/1/WHO_CDS_CSR_EPH_2002.23.pdf

World Health Organization. 2010. Report of the first meeting of the Leptospirosis Burden Epidemiology Reference Group. Switzerland, Geneva. Retrieved from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44382/1/9789241599894_eng.pdf

Zhang, W., Zhang, N., Wang, W., Wang, F. et al. 2014. Efficacy of cefepime, ertapenem and norfloxacin against leptospirosis and for the clearance of pathogens in a hamster model. Microbial Pathogenesis. 77: 78-83. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2014.11.006

Zhao, J.F., Chen, H.H., Ojcius, D.M., Zhao, X., Sun, D., Ge, Y.M., Zheng, L.L, Lin, X., Li, L.J and Yan, J. 2013. Identification of Leptospira interrogans Phospholipase C as a Novel Virulence Factor Responsible for Intracellular Free Calcium Ion Elevation during Macrophage Death. PLoS One. 8(10): e75652. Available from: DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075652